Interlocked min/max on HLSL single precision floats (Part II)

This is a quick (and final) continuation of the previous post on HLSL interlocked min/max floats.

As a recap, the goal is to leverage some properties of the bit-representation of an IEEE 754 float

to perform atomic min and max operations on floating point values. In the previous post, we used some bit-twiddling to map the entire

floating point range to a 32-bit unsigned value, at which point existing InterlockedMin and InterlockedMax intrinsics were usable.

Here, I wanted to address an even more efficient way to perform this trick (under certain conditions), address an important footgun with the more efficient alternative,

and also mention other floating point formats.

Signed interlocks

Let’s remind ourselves how the two’s complement representation of signed integers work (the only signed-int representation we care about in practice). The positive range of a signed 32-bit int extends from 0x00000000 and reaches 0x7fffffff, behaving exactly like an unsigned int in this range. The first negative value (-1) has a binary representation of 0xffffffff, followed by -2 (0xfffffffe), and continuing to the smallest possible negative value represented by 0x80000000.

Compared to floating point numbers, in the positive range, signed ints possess the same partial ordering. That is, when two floats $f_0$ and $f_1$ such that $0 \leq f_0 \leq f_1$ are bit-cast to signed ints $s_0$ and $s_1$, we know that $s_0 \leq s_1$. This relation does not hold for negative floating point values, however, unless we invert all bits in the floating point input except for the sign bit.

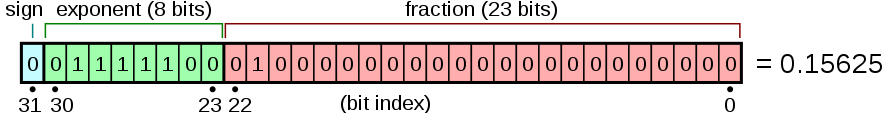

To see this, here’s the binary representation of a single precision float (as we saw in the previous part):

(image reproduced from wikipedia’s IEEE 754 binary32 article)

The smallest negative value possible ($-\infty$ or -1.#INF) has all bits set except for the fraction bits (setting all exponent bits

and any fraction bits produces a NaN). In contrast, the negative number closest to zero has the sign bit and least-significant bit

set. Put another way, signed ints wrap at 0x7fffffff, with the next increment producing INT_MIN. Floats on the other hand do not wrap

in the same way, and after 1.#INF, the next non-nan number isn’t -1.#INF, but -0.f instead.

In practice, what this means is the following:

- If all your floating point inputs are positive, you can just cast it to an

int, do a signedInterlockedMinorInterlockedMax, and everything will work as indended. Casting the result from anintback to afloatwill produce the correct result. - If all your floating point inputs are negative, you can also just cast it to an

int, but you should swap uses ofInterlockedMinforInterlockedMaxor vice versa. This is equivalent to introducing a minus sign and leveraging the method above, but without any arithmetic costs. - If your floating point inputs might be positive or negative, you could check the sign bit an invert all other bits, or simply use the order-preserving unsigned mapping used in the previous post (which can avoid the conditional altogether). I prefer the unsigned mapping which avoids the conditional in this case.

Here’s what the above points look like in code:

groupshared int lds_min;

groupshared int lds_max;

[numthreads(64, 1, 1)]

void CSMain(uint dtid : SV_DispatchThreadID, uint gtid : SV_GroupIndex)

{

if (gtid == 0)

{

// The first thread in the group initializes our LDS values to

// INT_MAX and INT_MIN respectively.

lds_min = 0x7fffffff;

lds_max = 0x80000000;

}

// Fetch or compute some float value using whatever means.

// This value MUST BE POSITIVE for this to work. Alternatively,

// if we know all inputs here are NEGATIVE, we could exchange our

// usage of InterlockedMin and InterlockedMax and everything would

// still work.

//

// If we expect both positive and negative inputs, we should just

// use the uint mapping from the previous post.

StructuredBuffer<float> buffer = ResourceDescriptorHeap[0];

float value = buffer[dtid];

// Ensure the initialization performed by the first thread in the

// group has occurred and the memory write is visible.

GroupMemoryBarrierAndGroupSync();

// Assumption: value >= 0.f

int ivalue = asint(value);

InterlockedMin(lds_min, ivalue);

InterlockedMax(lds_max, ivalue);

// If instead we knew that value < 0.f, we could do this instead

// InterlockedMax(lds_min, ivalue);

// InterlockedMin(lds_max, ivalue);

GroupMemoryBarrierAndGroupSync();

if (gtid == 0)

{

// Now you can easily produce the min and max values across

// the group with a simple bit-cast.

float group_min = asfloat(lds_min);

float group_max = asfloat(lds_max);

}

}

With this, you should be equipped to know when to take this “signed bit-cast” shortcut.

The footgun and how to sidestep it

There is an important thing to keep in mind when using signed interlocked/atomic intrinsics. This is an HLSL-specific footgun that isn’t strictly related to the topic above, but important to mention in case you do decide to try and invoke signed interlocked ops.

Take a look at the following snippet and try to answer the question in the comment.

As a reminder, RWByteAddressBuffer supports both InterlockedMin and InterlockedMax

as intrinsic methods, and both methods possess several overloads. One set of overloads

contains two parameters to pass the offset and value. All overloads in this set have a signed

and unsigned version. The other set of overloads contains three parameters to include the original

value as the third parameter. All overloads in this set also posses signed and unsigned versions.

RWByteAddressBuffer buffer;

[numthreads(1, 1, 1)]

void CSMain()

{

// For each of the interlocked min operations seen below, will the compiler

// emit a signed atomic min, or an unsigned one?

int value = 1;

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, value);

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1);

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1u);

buffer.InterlockedMin(1, -1);

// Now do the same exercise for the overloads that accept an extra parameter

// that will receive the original value prior to the atomic operation.

int original;

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, value, original);

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1, original);

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1u, original);

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, -1, original);

}

And here are the answers:

RWByteAddressBuffer buffer;

[numthreads(1, 1, 1)]

void CSMain()

{

int value = 1;

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, value); // Signed (good)

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1); // Unsigned (?)

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1u); // Unsigned

buffer.InterlockedMin(1, -1); // Signed

int original;

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, value, original); // Signed

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1, original); // Unsigned (?)

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1u, original); // Unsigned (?)

buffer.InterlockedMin(0, -1, original); // Signed

}

A few of these answers should be quite surprising, and at least one of these answers should (in my opinion), not compile, but instead it compiles with a surprising result.

Notice that buffer.InterlockedMin(0, 1) produces an unsigned atomic min operation. This occurs because,

unfortunately, all numeric literals in HLSL without a numeric suffix are represented as the largest unsigned integral type needed to accommodate the specified value.

No available suffix produced the widest signed type possible. This is in contrast to C, where literals without a suffix are interpreted as a signed numeric value.

As a result, with the two parameter overload of RWByteAddressBuffer::InterlockedMin (and other similar methods), there is no way to specify the

signed overload without either a direct cast (e.g. buffer.InterlockedMin(0, (int)1)), or by declaring the value as a separate explicitly typed signed variable (as in buffer.InterlockedMin(0, value)).

The reason buffer.InterlockedMin(0, -1) selects the signed overload is because there is no unsigned type that can contain -1, so in a sense, only negative

signed values can be represented by numeric literals.

Furthermore, in the second set of examples with the original parameter, note that even though original is typed as a signed integer, the type of original seems

to not participate in overload resolution at all. In my opinion, the overload selection would ideally constrain the types of value and original to be the same (and throw a compiler error otherwise),

but for now at least, that isn’t the case.

The moral of the story here is that if you do any sort of overload resolution that depends on the signed vs unsigned nature of the inputs, be very careful when passing literal values to such overloads. This extends beyond the specific example here to your own usage of argument-dependent lookup. This may be fixed in the future, but for now, feel free to watch this issue to track future discussion or progress.

Other float types

As a final discussion topic, but it’s worth metioning that the IEEE 754 half precision and double precision formats are functionally identical to the single precision format we’ve been looking at, with bits simply removed or added to the exponent and fraction fields respectively.

For comparison:

- A

halfconsists of a sign bit, 5-bit exponent, and 10-bit fraction - A

floatconsists of a sign bit, 8-bit exponent, and 23-bit fraction - A

doubleconsists of a sign bit, 11-bit exponent, and 52-bit fraction

This means that in a world where “half” or “double” atomic ops existed, you could adopt the techniques above for half and double-valued inputs also.

In practice, half inputs should just be widened to 32-bits, at which point everything we’ve talked about with respect to single precision floats apply.

For double inputs, you would need to check if 64-bit integral atomics are available, and then adapt the bit-twiddling trick we’ve used to accommodate the different bit pattern.

This should be easy enough to do, but note that I have yet to need this type of thing myself.

Conclusion

At this point, I hope I’ve exhausted the useful bits of information we could try and consider regarding interlocked min and max ops on floating point data in HLSL. The takeaway might be that we should all be mindful of the binary representation of our data, but while that may be true, I do hope that in the future, such “tricks” won’t be necessary. A casual reader might assume that I am somehow a big fan of tricky or clever code. In reality, I’m merely a pragmatist and interested in solving the problem in front of me. If “ugly code” gets the job done without an easy-to-maintain equivalent, I’m not going to say “no,” but it’s important to explore easier-to-maintain alternatives if they present themselves. For now though, we have a mental model for why this works, and hopefully that mental model will be of use if you need to adapt these techniques for your own particular use cases.