Interlocked min/max on HLSL single precision floats

For quite some time now, HLSL has supported a variety of intrinsics for performing atomic operations on a given address.

The address typically refers to groupshared memory (sometimes referred to as “LDS” or “shmem” depending on the color of your GPU)

or a location in an RWByteAddressBuffer (or some other uint or int typed-resource).

These intrinsics are extremely useful in a variety of situations – here are a couple common ones:

- Incrementing a counter in order to allocate memory on the GPU (e.g. to implement order-independent transparency)

- Summing a computed value across all invocations (e.g. to count the number of occurrences of an event)

There is an unfortunate limitation with the interlocked intrinsics at the moment, however.

Namely, while the interlocked intrinsics did gain 64-bit support

and certain float

atomic capabilities, we still can’t use the general reduction intrinsics (add, min, max) with vector<float, N> inputs (some of which have hardware support).

For example, if you study the RDNA2 ISA (warning, big PDF),

you will find instructions such as BUFFER_ATOMIC_FMIN among others (which come fully featured with NaN, INF, and denormal handling).

While atomic float sums are understandably unavailable, it turns out there is a somewhat (well-?) known trick

to perform atomic min and max reductions on floats. You would want this, for example, in order to compute the max or min luminance in a frame (among other useful quantities).

The trick

So as not to bury the lede, here’s the code to perform a floating point min and max operation (ignoring NaNs and subnormals and such for now). Note that there are many ways of expressing the same idea, and some of the code below is repeated for the min and max case to be explicit. The code is written in this way for clarity (and doesn’t handle NaN values, which can be handled in a couple ways described later), so please adapt it for your own needs.

groupshared uint lds_min;

groupshared uint lds_max;

[numthreads(64, 1, 1)]

void main(uint group_index : SV_GroupIndex)

{

if (group_index == 0)

{

lds_min = 0xffffffffu;

lds_max = 0;

}

// Suppose we want to compute the min and max values of fvalue across

// all invocations in the group.

float fvalue;

// Perform a bitwise cast of the float value to an unsigned value.

uint uvalue = asuint(fvalue);

if ((uvalue >> 31) == 0)

{

// The sign bit wasn't set, so set it temporarily.

uvalue = uvalue | (1 << 31);

}

else

{

// In the case where we started with a negative value, take

// the ones complement.

uvalue = ~uvalue;

}

// This barrier ensures that invocation with group index 0 has

// run and initialized our LDS values.

GroupMemoryBarrierWithGroupSync();

uint original_min;

InterlockedMin(lds_min, uvalue, original_min);

uint original_max;

InterlockedMax(lds_max, uvalue, original_max);

// Ensure interlocked operations have finished across all invocations

// in the group.

// Reminder that interlocked operations do not imply a memory or

// execution barrier!

GroupMemoryBarrierWithGroupSync();

if (group_index == 0)

{

float group_min;

float group_max;

if ((lds_min >> 31) == 0)

{

// The MSB is unset, so take the complement, then bitcast,

// turning this back into a negative floating point value.

group_min = asfloat(~lds_min);

}

else

{

// The MSB is set, so we started with a positive float.

// Unset the MSB and bitcast.

group_min = asfloat(lds_min & ~(1u << 31));

}

// Do the same conversion operation for the max value.

if ((lds_max >> 31) == 0)

{

group_max = asfloat(~lds_max);

}

else

{

group_max = asfloat(lds_max & ~(1u << 31));

}

// Now, group_min and group_max refer to the min and max

// floating point values of `fvalue` across the group.

}

}

You can, of course, write this code in a more concise manner (I suggest functions to prepare a

floating point value as a uint for the min/max reduction and another function to convert back).

The structure of the trick is essentially:

- Do a bitwise cast of your

floatvalue to auint, and do some prep work afterwards. - Use

InterlockedMinandInterlockedMaxwith auintreference address along with your converteduintinput. - Read the value back, applying the inverse operation from the first step to convert the

uintback to afloat.

If all you want to do is apply the trick, you could probably stop reading here and adapt the technique to your own code. But I recommend you read further to convince yourself that it works, as well as consider how “special” float values are handled.

This code is available for experimentation here on Compiler Explorer.

Why does this work?

The general idea is that we want to map the entire set of single-precision floating point values to

uint values such that monotonicity is preserved.

That is, given two float values $f_1$ and $f_2$, we want to find some bijective mapping $U$

from float values to uint values such that the following statement is true: $f_1 < f_2$ implies

that $U(f_1) < U(f_2)$. To convince yourself that this is a sufficient condition, you can make the

following observations:

- We need the mapping to be a bijection so we can reverse the mapping later.

- If the relative order is preserved after the mapping, we know that $\textbf{argmin}(f_1, f_2)$ will

be equal to $\textbf{argmin}\left(U(f_1), U(f_2)\right)$. Similarly, the same relation will hold for the

maxoperation.

Combining these two observations, we can write:

\[\begin{aligned} \textbf{min}(f_1, f_2, \dots) &= U^{-1}\left(\textbf{min}\left(U(f_1), U(f_2), \dots\right)\right) \\ \textbf{max}(f_1, f_2, \dots) &= U^{-1}\left(\textbf{max}\left(U(f_1), U(f_2), \dots\right)\right) \end{aligned}\]This more or less follows the structure of our code above, except expressed mathematically. Great! Now all we have to do is find a mapping $U$ that satisfies our order-preservation condition.

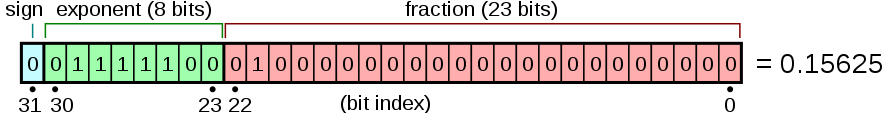

Recall that the bit layout of a single-precision float looks like this:

(image reproduced from wikipedia’s IEEE 754 binary32 article)

and suppose we tried to just use asuint as our map $U$. The first problem we’d run into immediately

is that all negative numbers mapped in this way become bigger than all positive numbers. Hence,

for positive numbers, our map should set the most-significant bit (MSB) and vice-versa.

Next, consider only the positive half-range for a moment. Notice that when the exponent increases, the value increases, and similarly, when the fraction increases, the value increases as well. In other words, the bits 0 through 30 in the positive half-range already exhibit increasing monotonic behavior when viewed as an unsigned integer.

The negative half-range behaves identically, except the values are monotonically decreasing when viewed as an unsigned integer. To fix this, we can simply invert all bits for negative values. This has the additional benefit of unsetting the sign bit, ensuring that all negative values are less than all positive values once the map is applied.

At this point, our candidate map $U$ should perform the following operations:

- If the sign bit is set (the input is negative), invert all bits.

- If the sign bit isn’t set (the input is positive), set the sign bit.

Hopefully, it’s clear that the outcome comparison operations should be unchanged when unsigned comparisons are performed on the output. The last check is to ensure that our map is bijective. That $U$ is a bijection should be immediately apparent though, given that the steps are trivially reversible.

With that, we have some mathematical justification for the “trick” we’ve implemented above, and can now

do interlocked min/max operations with float values at the cost of a few conversion operations.

Special values

It may or may not be immediately obvious how this trick works when considering NaN values, subnormals, and infinities. Let’s tackle each case one-by-one.

NaN values

The first question to ask is, what should the result of a min or max operation be when one or more of the

input values are NaN? There are at least three possible answers:

- NaN input values are ignored

- If any input to a

minormaxoperation is NaN, the result should also be NaN - Undefined (i.e. you promise not to provide NaN inputs)

Of course, it’s possible to implement any of these behaviors ourselves programmatically (although I would prefer option 1 or 2 depending on the situation personally). Further, there isn’t a “right” answer for all scenarios. After all, this isn’t an operation specified by IEEE 754, and different languages and runtimes have historically made different choices in this regard.

That said, let’s see what happens to NaN values under our mapping without any changes.

A NaN value has all exponent bits set (0b11111111) and a non-zero fraction.

However, the sign bit may or may not be set depending. This means that by default, our mapping will has the unfortunate property

that a NaN value might propagate (i.e. compare greater-than or less-than other non-NaN values) depending on whether we are performing a min or max reduction. With this understanding,

we can mitigate this problem by handling NaNs in one of the following ways:

- Do an

isnancheck of the input first, and skip the interlocked operation if a NaN is encountered. - Do an

isnancheck of the input first, and then set or unset the sign bit to ensure the NaN propagates. - Do nothing, and just expect things to break if a NaN is fed into the algorithm.

As a reminder, the snippet above does the third option for simplicity, so do adapt the code to implement one of the other options (or something else entirely) depending on your requirements.

Infinities

Single-precision floats have both a positive and negative infinity (spelled 1.#INF and -1.#INF in HLSL respectively), both of which have unique bit-patterns.

In both cases, all exponent bits are set and all fraction bits are unset.

In addition, the sign bit is set as you would expect to denote a positive or negative infinity.

Given that, we fortunately don’t have to make any special changes to our mapping to accommodate infinities. Unsigned numbers that are greater than or less than $\pm \infty$ are, in fact, NaN values that should be handled in one of the methods prescribed above.

Subnormals

Subnormals (also referred to as denormals) have no exponent bits set, and one or more fraction bits set.

Thankfully, positive subnormals compare greater-than zero, and negative subnormals compare less-than zero as you would expect.

Similarly, subnormals compare as you’d expect with the positive and negative normal numbers that are closest to zero after

unsigned conversion. As with 1.#INF and -1.#INF, no special handling of subnormals are needed. Note that if this

behavior may not actually be observable in your shader if you’ve compiled with default settings that have enable FTZ

(subnormal flush-to-zero).

Signed zero

One last point to consider is the effect of $U$ on signed and unsigned zeroes.

Our $U$ map converts +0.f to 0x80000000 and -0.f to 0x7fffffff. The unsigned representations are off by 1,

and directly in the middle of the range of possible unsigned values.

Note that in this representation, we actually have that U(-0) < U(+0), so technically, our interlocked

min/max operation induces an ordering between differently signed zeros! This is unlikely to be actually significant in your code,

but it may be useful to remember in case you expected something to be a no-op. I’m mentioning this point

here because signed zeroes are the one technicality I am aware of where the ordering constraint of $U$ isn’t

quite true. That is, -0.f is not strictly less than +0.f and vice versa, but order between -0.f and +0.f

is suddenly induced after our $U$ map is applied. I say this is unlikely to matter, however, because after we

invert the mapping (applying $U^{-1}$), any ordering we temporarily imposed between positive and negative

zero vanishes.

Performance

The impact of the code is some overhead needed to perform the mapping. The cost of the inverse mapping is typically negligible, since this is only felt when we read the value back after the reduction has finished. In an ideal scenario, HLSL exposes the hardware intrinsic for atomic min/max directly, at which point the need for the mapping (and NaN check) goes away completely. Generally though, I haven’t been able to measure the impact of this code because when you’re shoving data into an atomic unit, you usually aren’t ALU bound.

As a bonus, here is the routine I use, which avoids the conditional branch in the code written above:

// Check isnan(value) before use.

uint order_preserving_float_map(float value)

{

// For negative values, the mask becomes 0xffffffff.

// For positive values, the mask becomes 0x80000000.

uint uvalue = asuint(value);

uint mask = -int(uvalue >> 31) | 0x80000000;

return uvalue ^ mask;

}

float inverse_order_preserving_float_map(uint value)

{

// If the msb is set, the mask becomes 0x80000000.

// If the msb is unset, the mask becomes 0xffffffff.

uint mask = ((value >> 31) - 1) | 0x80000000;

return asfloat(value ^ mask);

}

You’ll find code similar to the snippet above elsewhere. Here’s a recent example mentioned by Aras that uses the same trick to perform floating point radix sorting.

Conclusion

In this post, we review a trick often used to perform atomic min and max operations on floating point values. My personal hope is that this trick will be obsolete, as modern GPU hardware can already perform these operations natively, without any cost needed to do the mapping described here. That said, for the time being, this trick is really useful, and the underlying concept is fairly easy to understand also.

From here, feel free to read part 2, where we discuss an alternative to this approach using signed interlocked operations instead, and discuss other floating point formats also.